Station No. 2: Helping Hands Korea

The musty underground air flared thickly through the subway and seeped into the remains of my sandwich. I hastily polished off my go-to dinner and hurried through Samgakji Station. Giving a quick prayer of thanks for the blessing of escalators, I stretched my tired legs and breathed deeply into the welcome night air.

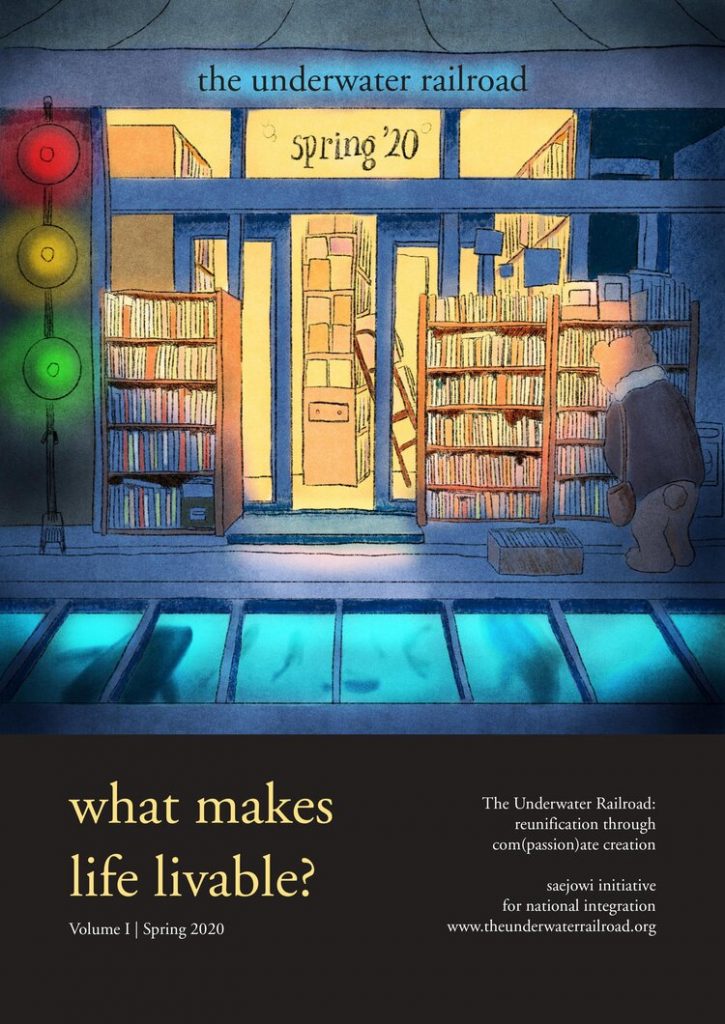

Catacombs, the meeting place for Helping Hands Korea (HHK), is tucked into a cobbled side alley with old-fashioned stories that sell keys and buy gold teeth. The opening is so narrow that I completely missed it the first time I came to the Catacombs. When I arrived, Tim and Sun Mi were already speaking with two of their regular couriers. They were Korean missionaries who delivered packaged seeds to North Korean workers in China, who would then smuggle the seeds back to their villages for planting.

“Oh, welcome, Esther!” Tim cried warmly. Every time I came to Catacombs, he greeted me as joyfully as if he was seeing me for the first time. Laughter comes easily to him, and he listens to every word others say with deep and seemingly genuine interest. A tall, broad-shouldered man in his ___, he sat comfortably on a wobbly stool that looked too small for him. “Please make yourself at home. This is my dear wife, Sun Mi.”

Sun Mi had been gone for the past several weeks, so it was the first time I met her. Her dark hair was knotted neatly back and her eyes were quick, observant, like the glistering edge of an uncut gem. “Annyonghaseyo,” she said briskly in Korean, then added in English, “He has told me a lot about you.” Her smile was unexpected and kind.

When the couriers had left, the three of us sat down at the tiny round tables and began chatting. It has been about a month or two since I began volunteering at Helping Hands Korea in my free time after work. HHK supports malnourished North Korean families through packaged seeds; it also works with people in China to help North Korean refugees escape safely through the East Asian version of the underground railroad. They hold seed packaging sessions each Tuesday at Samgakji Station, in a tiny, placard-less gallery the size of a bathroom, but a steady stream of visitors arrive every week: TIMES reporters, expats, English teachers, researchers. As people pour spoonfuls of spinach seeds into small plastic bags, they exchange information about North Korea. The meetings are not explicitly Christian, nor are most of the visitors Christian themselves, but Tim always ends the meetings with a short prayer. He is also not at all shy about declaring that he has dedicated himself to this work simply and solely because of his love for Jesus.

“My hope is that Catacombs can combine the spiritual and practical humanitarian,” he explained. “I have great respect for the North Korea prayer meetings that go on throughout South Korea–obviously, I believe sustained, dedicated intercession is important. But I think young people need to see practical change happen, along with the spiritual. So this meeting has evolved into more of an open forum, a crossroads where people of different beliefs and backgrounds can meet and share their passion for North Korea. Some believers who expect an explicit worship environment can find it hard to adjust to the fact that many people here are not believers, but I wanted to make a place where we could interact with ideas and strategies, and also touch the lives of several hundred families by the end of the conversation.” He pointed to the seeds and smiled.

Sun Mi, he adds, is “the secret weapon of the organization.” Tim speaks primarily in English, and Sun Mi is often his quiet translator. “Her English is so much better than my Korean,” he laughed. She is well trusted by their Korean partners and couriers, and active in doing behind-the-scenes work. Tim went on enthusiastically: “I might be on the cover of TIME magazine, but Sun Mi is really the one counting the seeds, setting up the containers, doing behind-the-counter work…”

Sun Mi tapped his knee gently, frowning. “Honey, it’s okay.”

“No, no, I’m not just saying this to make you feel good. It’s the truth!” Tim exclaimed.

Sun Mi shook her head. “No, no. It’s okay. He does good job.” She waved at Tim, and seemed satisfied to let the matter rest there.

I smiled at Sun Mi and asked her how she met Tim. “He was my Bible teacher in Myeong-dong,” she replied.

“Yes, I did work with South Koreans then. There was something that drew me to Koreans that I just can’t describe.”

“Honey, obviously. You married one,” Sun Mi observed dryly.

We all laughed, and Tim protested, “Well, that’s not the only reason!” I asked Sun Mi how she came to believe in God, as she had been the only Christian in her family.

“I met Jesus through the missionaries at Myeong-dong. There was a big language barrier, since I didn’t speak English, and they were foreigners. But even though we didn’t understand each other completely, I can’t explain it, I felt so much love from them. They poured so much patience on me, even though I was a rebellious, naughty girl. I gave them a hard time.” She grinned wryly. “But they gave me so much love, and I could feel it wasn’t just their love. It was God’s love. So I thought, ‘This is my time, I guess.’ And I said yes to God.”

Tim said that he was “awakened to God’s love” in the spring of 1972 at the State College of Michigan. “I was 21, and growing more and more aware of an emptiness inside me,” he said. “I was old enough to make a couple of mistakes and realize I was a sinner. All the same, I was not an easy fruit to pick off the tree, so to speak.” He laughed. “One time my Christian friends witnessed to me for four hours. I had worked my way through college, and I was a good student, and I had so much intellectual baggage I couldn’t leave behind. But I just sensed…that these people are so happy. They had a freedom and a joy I recognized I didn’t have. So when they asked if I wanted to pray for salvation with them, I said, ‘Well, I don’t believe in God.’ But I prayed, ‘God, if you exist, then please manifest yourself to me.’ And nothing spectacular happened. No trumpets or fireworks or anything. But I will always remember–I looked up, and saw these shafts of sunlight coming through the tall windows of the Student Union building. And something about that resonated with me, as if I knew that some light was beginning to enter my life.”

Tim gazed upward with his eyes half-closed, as if still feeling the warmth of those rays.

“When I went back to my room, I opened the Bible and began reading, and the words seemed to jump off the page at me. It was as if they were alive. It wasn’t a particularly emotional experience, but it was real, and it was overwhelming. And as I studied the Bible for the next few years, a relationship with God began that transformed my life.”

He said that when he told his parents, they “couldn’t make heads or tails of it! They fell off their chairs, so to speak, in shock. World War II had been very hard on my father’s faith, and he still struggled to reconcile the horrible things he had seen with his beliefs, so he didn’t want to accept that I was dropping out of college to become a missionary.” Tim paused. “One of the greatest joys of my entire life was the moment I led my own father in his prayer for salvation, accepting Jesus into his life.”

We were hushed, reflecting on his story. After a short silence, I spoke up.

“Tim, I think many people struggle with the same problem. It’s tempting to look at North Korea and say, ‘If there’s a God, how can this happen?’ What would you say to that?”

Sun Mi sighed, and Tim pondered this soberly. “We were created with free will, and sadly, some people or governments make consistently bad choices of oppression and control. So I would say that the consequences of these choices are our responsibility, not something we can blame God for. If anything, my experience with helping North Korean people shows that the Bible is true in saying that there is a darker side of human nature, and that we live in a terribly broken world. Now, I don’t think I’m naive about the brokenness, but I also trust the Bible when it says that we have a role in bringing light into the dark spaces. I personally don’t struggle with the why so much as the how. How can we respond to these problems? How can we reach out and show Jesus’s love?”

I turned to Sun Mi, and she nodded. “Yes. We do what we can. If this is the situation, we have to just do our best, I guess.”

I considered their words. “You’re right, Tim and Sun Mi. I suppose we could spend a lot of time arguing about what’s going on right now, but the important thing is to do something about it.”

“Yes. That’s why I like the expression of, if I may, ‘Christian faith with its sleeves rolled up.’ As Christians, we need to take Jesus’s light–because it really is His light, not mine, not ours–into the darkest places. And as the Bible says: where sin increased–”

“–grace increased all the more,” I finished, lifting my eyes. Tim and Sun Mi smiled silently, all of us holding carefully onto the grace dwelling in our devastated world. Then the door tinkled open with the first Tuesday member, Sun Mi and I poured out the radish seeds, and another Tuesday Catacombs meeting began.

If you would like to read the full issue of Volume I (Spring 2020) of the Underwater Railroad, click here.